Overview of the history of the Institute

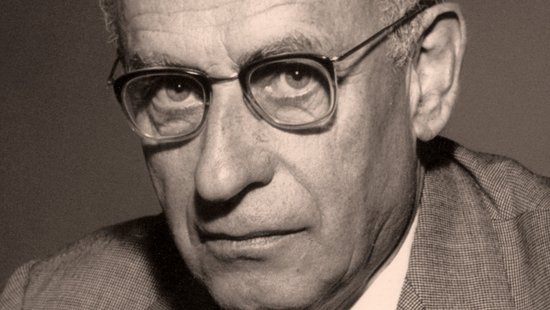

As early as the beginning of the 1990s, the historian Stefan Wulf was commissioned to research the history of the Tropical Institute from the end of the First World War to the end of the Second World War on the initiative of the then Ministry of Labor, Health and Social Affairs of the Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg. In 1994, Stefan Wulf presented the study “Das Hamburger Tropeninstitut 1919-1945: Kulturpolitik und Kolonialrevisionismus nach Versailles”, published by Dietrich Reimer Verlag (German only).

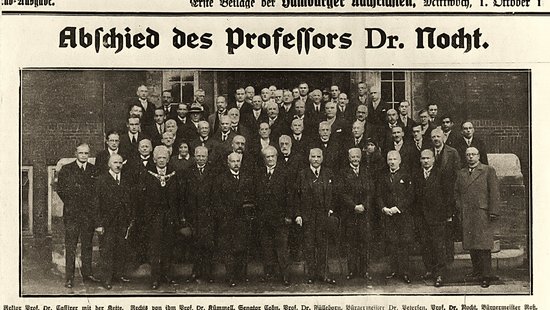

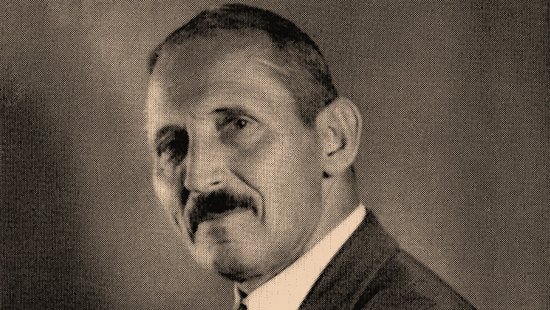

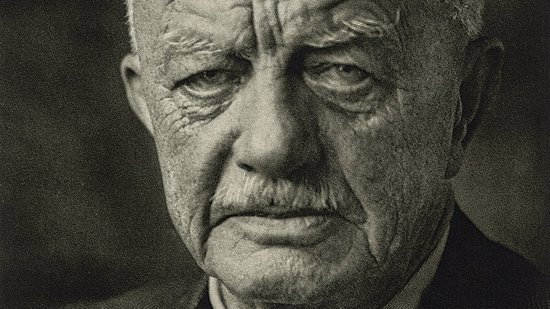

In the context of the current discussion on the reappraisal of German colonial history, and in particular Hamburg's colonial legacy, the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine has continued its research into its history and commissioned the Research Centre for Contemporary History in Hamburg to prepare an expert report on the first director, Bernhard Nocht. This report can be downloaded here:

Bernhard Nocht as the namesake of the Institute for Tropical Medicine? Expert opinion on the attitude of the tropical physician towards racism and National Socialismby Thomas Großbölting. Research Centre for Contemporary History in Hamburg.

At the same time, the research centre for Hamburg's (post-)colonial heritage has published a comprehensive biography of Bernhard Nocht by Markus Hedrich.

This and other publications about the institute can be found on our library page.

The "Institute for Maritime and Tropical Diseases" began its work on 1 October 1900, with 24 employees. Today, more than 400 staff work at the "Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine" (BNITM), making it Germany's largest institution for research, care and teaching in the field of tropical diseases and emerging infectious diseases.

Origins in colonial times

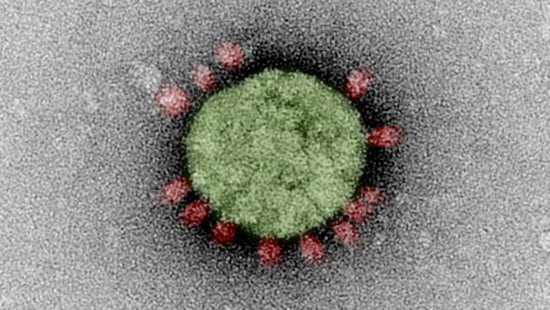

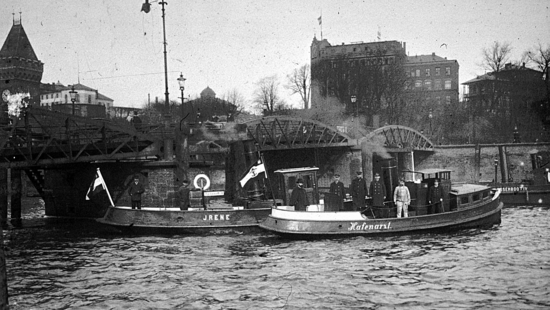

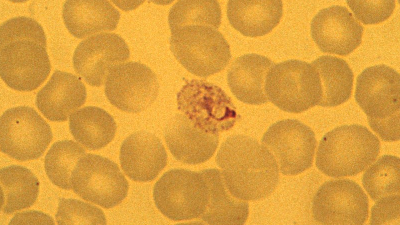

Like all tropical institutes founded around 1900, the BNITM has its roots in the colonial era. In the course of the colonial conquest and exploitation of countries and territories in the so called Global South, ship crews and travellers increasingly brought unusual infectious diseases to Germany via the port of Hamburg. The founding purpose was therefore the research and control of tropical pathogens.

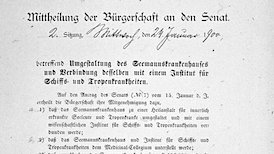

The cholera epidemic of 1892 in Hamburg provided the final impetus: about 9,000 people had died of the disease. The economic damage was also immense. Russian sailors or emigrants in transit had probably brought the bacterium with them. Because of the outdated drinking water system, it was able to spread quickly. The city of Hamburg was forced to restructure its health system and appointed Bernhard Nocht as harbour doctor. A little later, the city's parliament decided to "restructure the Seamen's Hospital and combine it with an Institute for Ship and Tropical Diseases".

History of the Institute

The new port doctor realised the urgent need for further training for doctors in dealing with tropical diseases. According to the principle of "research, cure, teach", the institute made research and teaching in the field of ship and tropical medicine its task in addition to patient care. After the experience of the cholera epidemic, similar outbreaks were to be prevented in the future. Hamburg's merchants also had an economic interest in the development of tropical medicine. They implemented new findings on the prevention of malaria and other diseases on their ships so that the crews remained healthy and efficient. The institute offered numerous continuing education courses for doctors in the early years and counted more than 800 participants by 1914. Research focused on laboratory studies of exotic pathogens and their vector insects. In addition, the institute conducted studies on travellers and seafarers with imported infections. Research visits to the tropics took place only very sporadically.

With the beginning of the war in 1914, the building was converted into a reserve hospital and research work largely came to a standstill. During the world wars, the institute endeavoured to maintain or regain access to the tropics in the German colonial territories: During the Weimar Republic, the economic and global political conditions on which the existence of the Tropical Institute was based had changed fundamentally. After the peace treaty of Versailles, the German Reich no longer possessed any colonies. German scientists were internationally isolated. The Tropical Institute no longer had a raison d'être. Its continued existence was uncertain.

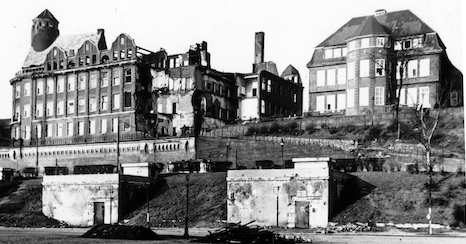

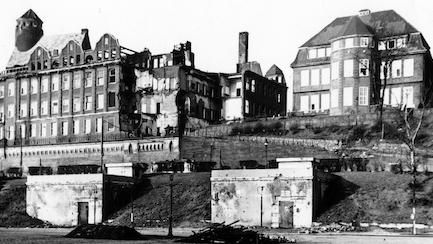

Under National Socialism, several Jewish employees were forced by the Nazis to leave the Institute. There is evidence of drug trials on the inmates of the Langenhorn sanatorium and nursing home and the testing of new cures on prisoners suffering from typhus in the Neuengamme concentration camp near Hamburg. The institute building was severely damaged during the nights of bombing in Hamburg.

Shortly after the end of the war, Bernhard Nocht and his wife took their own lives. In a farewell letter to their children, they wrote that they did not feel up to the task of reconstruction.

Reconstruction and reorientation

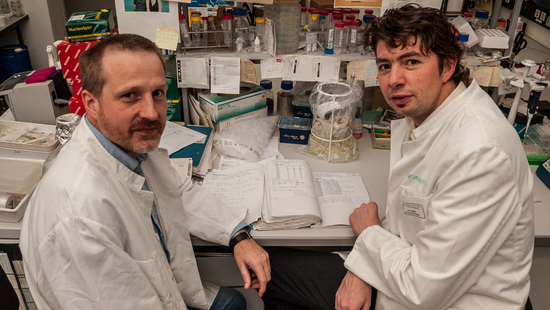

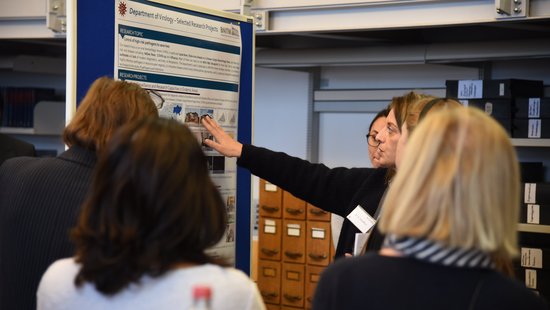

With the liberation by the Allies in 1945, a phase of reorientation began at the Bernhard Nocht Institute. The directors of the Institute cultivated international contacts and endeavoured intensively to establish the first research collaborations with South America, Asia and Africa. In 1968, the Institute established its first research station in Liberia, West Africa, and a few years later took over the management of the clinical laboratory of the Albert Swiss Hospital in Lambaréné, Gabon. With the founding of the Department of Virology in the 1950s, the Institute received one of the first electron microscopes in Germany and acquired the corresponding expertise. As a result, it was also able to significantly support the establishment of electron microscopy at the Instituto Oswaldo Cruz in Rio de Janeiro.

However, following an external assessment in 1986, the German Council of Science and Humanities determined that the BNI did not fulfil the expectations of a modern non-university research institution. Tropical medicine had failed to utilise new disciplines such as immunology or molecular biology for its research.

This was to change in the 1990s. The institute received modern laboratories, was able to attract young international scientists and developed modern research concepts. It also succeeded in establishing research cooperation with various countries. For example, the Kumasi Centre for Collaborative Research in Tropical Medicine (KCCR) was opened in Ghana in 1998. It is run in partnership by BNITM, the University of Kumasi and the Ministry of Health of the Republic of Ghana. These projects directly contribute to building research infrastructures in Africa.

Research for Global Health

Today, the BNITM is one of the world's leading institutions in the field of tropical and emerging infections. The institute conducts state-of-the-art laboratory research and uses the latest methods in immunology, molecular and cell biology. As a founding member of the Centre for Structural Systems Biology (CSSB), the BNITM maintains laboratories on the DESY campus in Hamburg Bahrenfeld. The scientists have access to the unique imaging techniques used for the latest research results in virology and parasitology. In addition to research in the laboratory, the BNITM carries out extensive research projects in Africa, Asia and Latin America. In cooperation with partner countries, BNITM conducts research on the epidemiology, therapy and control of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) such as malaria, worm infections or haemorrhagic fevers, among other things.

![[Translate to English:] LOGO NRZ Blaue Weltkugel mit Symbolen in Weiß. Dazu die Bezeichnung des Zentrums in schwarzer Schrift rundherum: Nationales Referenzzentrum für tropische Infektionserreger](/fileadmin/_processed_/e/5/csm_NRZ_Logo_16x9_d7289c46ae.png)